Hungry Freaks, Daddy: The Disturbing World of Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention's "Freak Out!"

…No, no, wait, come back, I swear it's really good

What do you make of all this freak stuff?

Obviously Zappa wasn't using the term in the modern sense of it, as in, like, sexually freaky. Turns out there's a substantial socio-anthropological sort of thing going on behind it. In the 1960s - specifically '66, the year just before the explosion of the psychedelic Summer of Love - there were, broadly, three kinds of people in a musician's worldview:

Squares - the purity-obsessed, high-socked, very moral, very US-flag-flying people who thought Elvis was too exciting and the Beatles were satanic. (True squares are rare in 2025, but you might catch a glimmer of the squareish aspect of the American psyche in the modern day (though in a completely different incarnation) with people who only listen to lowest-bidder, radio-friendly white-person music and/or celebrity-worship certain pop musicians, both in ignorance of other musical forms and in a sense that it's somehow morally wrong to have a more diverse taste.) Squares ran conventional society ("the man," "the establishment"), and were represented by both major political parties, but especially Republicans (Reagan was just about to be elected governor of California). Squares hated both hippies and freaks.

Hippies - you know what a hippie is, right? The Grateful Dead fan, the tie-dye and long hair wearer, the acid dropper. They weren't important on a national level until the Summer of Love, at which time Zappa would grow to hate them (more on that later), but he knew a fair few living in mid-'60s SoCal, especially as a member of the counterculture.

The other half of the counterculture, sharing many similarities with hippies, were the freaks, the subject of this article. Zappa defined these people as Los Angeles types who cared more about their appearance than the San Francisco hippies; I'd say they were more like proto-punks. As opposed to hippies' specific drug habits, freaks were often either sober (Zappa famously never did drugs, perhaps forecasting the "straight edge" punks like Fugazi's Ian Mackaye) or off some really weird shit. Freaks also celebrated uniqueness, self-expression, and non-conformity much more than the slightly cultish collectivism of hippies. While Zappa had complete creative control later in his career, on this album his backing band, the assortment of Inland Empire freaks known as the Mothers of Invention, had a lot of input on the creative process, taking center stage to the point where the album is only credited to them as a whole, not Zappa - i.e., it’s a group effort, not the cult of the frontman that some hippie bands had.

More people were freaks than you'd imagine - Hunter S. Thompson of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas fame once tried to register a "Freak" political party in the town of Aspen, Colorado, and even Jimi Hendrix, despite his Woodstock credentials, said he "would let his freak flag fly" in the lyrics to "If 6 Was 9" (1967).

So is Freak Out! some sort of freak declaration of independence? Yes and no. On one hand, it is extremely radical music - the second rock double album in history (issued mere days after Dylan's Blonde on Blonde) and arguably the first ever rock concept album, containing a substantial amount of difficult avant-garde music of the sort that had never before been released under a non-classical label, and lyrically tied up with political repression and anti-authoritarianism. On the other hand, it's just a really good piece of music that happens to depict a certain subset of people at a certain time in history. Also, uh, half the album is decidedly un-freak.

Yeah, did I forget to mention? Only half of this album (the first and last few songs) is actually Zappa-style freakery. The gigantic, swollen middle mass is all satire of the boring, square-oriented music available on the radio in SoCal at the time - complete with comically stupid lyrics and a dramatic, Beach Boys-style string/horn section. Most of them are about divorce/breakups/girl trouble, seemingly because he was going through a bad divorce at the time, though the satire is usually set up in such a way that it makes the narrator the bad guy in the situation. It's legitimately good satire, too, made with a clear love of the genre it's affectionately mocking. Both the good and bad aspects are exaggerated, really. Many of the songs still hold up to modern radio music - I thought of the nasal "I thoughtchoo were my TEENAGE THRILL!" ad-lib in "You Didn't Try To Call Me" when I heard Katy Perry's "Teenage Dream" in the dining hall a few days ago.

On the other hand, sides 3 and 4 of the double album are composed of sound collages, aka musique concrete, a series of ominous-sounding noises from disparate sources assembled together - an art form previously restricted to the European avant-garde aristocracy, championed by only obscure weirdo composers such as Edgard Varese. (Zappa actually spoke to Varese's wife once - as he says in his book, his mother gave him a then-expensive long-distance phone call to the composer's New York residence when he was a teenager in California, but he wasn't home at the time). The Zappa take on these is grimy and dark, including vocals and taking on more of a narrative form than the more abstract collages of Varese and contemporaries like Pierre Schaeffer (have you ever heard of a more European Avant-Garde Person name than "Pierre Schaeffer"??) I made a diagram:

Note that the individual track lengths mean Zappa could have made a single LP of just the freakiest material, without the satirical pop stuff, and it probably would have been less of a hassle, but he actively chose to include that stuff, so we're evaluating it right along with the rest of the album.

I interpret Freak Out! as a concept album. In his invaluable memoir The Real Frank Zappa Book, he says that every song on it "is about something." The album, taken as a whole, creates a powerful snapshot of life as a countercultural freak in an unintelligent and superficial society. I like to see it as a rock opera that follows the events of a single day in some sort of freak revolutionary's life:

-First three songs: Establishing the scene, getting orders, setting up

-Middle section: Day-to-day life, pretending nothing is amiss while resenting the powers that be (the divorce songs can be interpreted as metaphorical, like what you're really getting divorced from is Society.)

-Side 3 and 4: The freak revolution - sort of a precursor to the Beatles' "Revolution 9," the sound collages show the chaos of the world

Of course, this is a little fanciful, but Zappa really did influence the Beatles - there's countless primary sources showing that the unified, conceptual nature of the album directly pushed them to make "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" more of a concept album. Well, Zappa actually influenced a ton of other people, mostly Europeans, as American composers at the time weren't quite at the level of being avant-garde yet. Listen to the "Return of the Son of Monster Magnet" and compare it to Faust's "Meadow Meal" (1971) - five years later, and yet barely at the level of the forward-thinking Californian.

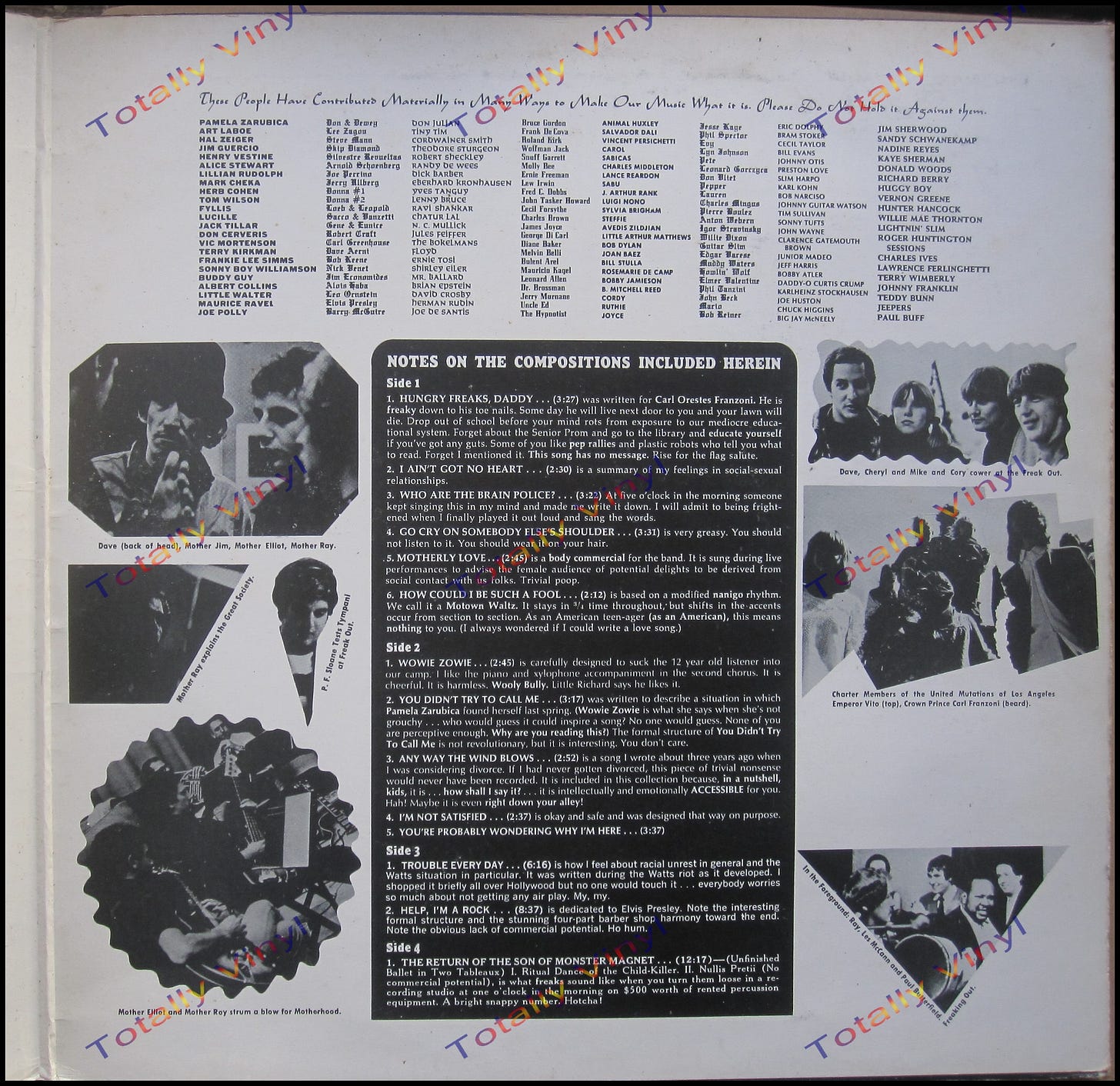

Let's take a look at the liner notes of the original pressing, available here:

Note the snappy, condescending nature of his notes for some of the songs, especially the satirical ones, with one-liners like "You don't care" and "As an American teenager (...as an American), this means nothing to you" popping up after any kind of musical description. This was music made by people who saw themselves as not understood by society. The autobiography, which I really can't recommend highly enough, goes into more detail on how he arrived at this worldview (among a bunch of other tidbits and thoughts about his opinions on everything going on in the world in the late ‘80s, when it was written - did you know he was friends with Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys?), but suffice to say every song, whether pop or avant-garde, is full of that dark sarcasm, a brave and eclectic first statement by a still scrappy and upcoming band.

Zappa would go on to have a long, decorated, multi-decade career, using the same sarcasm against everything from hippies (the album "We're Only In It For The Money," recorded during the Summer of Love, takes down the whole movement) to Valley-girl slang (his latter-day hit "Valley Girl"). He also embraced progressive rock and jazz influences in addition to classical and the blues, leading later efforts to be famously musically complex, with a ten-piece band playing in shifting odd meters.

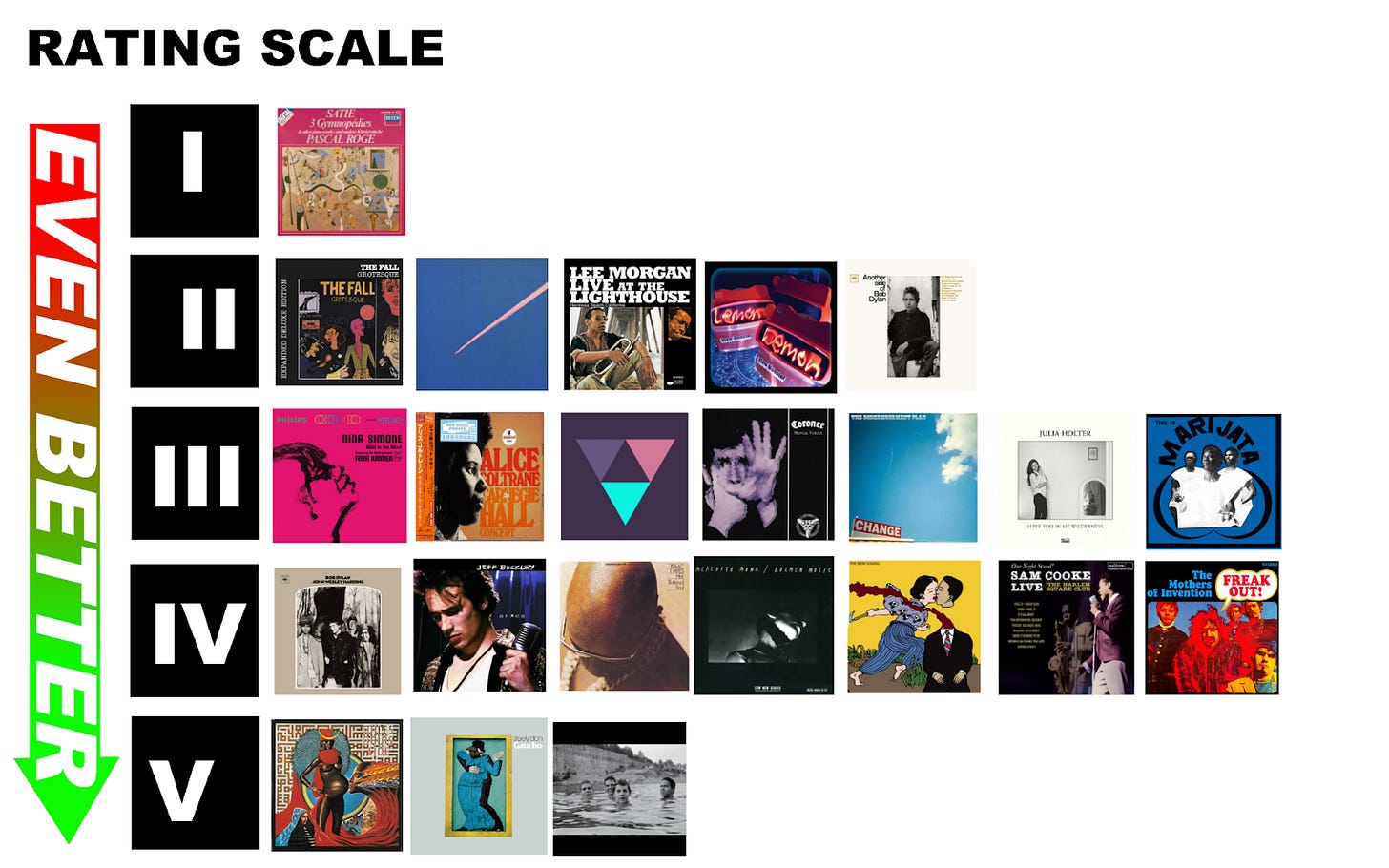

Overall, I would say this album is a substantial, bold artistic statement, and one of the finest albums released that year (even holding up to such landmarks as Pet Sounds and Revolver while allegedly consuming none of the massive amounts of LSD required to create both.) I would give it a IV on the rating scale, putting it alongside fellow American avant-garde composer-performer Meredith Monk's "Dolmen Music":